I found out about Bourdain’s death in the strangest way.

I found out about Bourdain’s death in the strangest way.

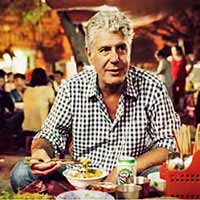

I was in the middle of a meeting when my phone rang. It was an editor from The Print. Did I want to do a piece about Anthony Bourdain, she asked. I said that no, I didn’t. I had never met him. I was not a particular fan.

“But, you know”, she continued, “what about his legacy and all that?”

Sorry, I responded. I really had no interest in a Bourdain piece. She was gracious and we ended the conversation.

I put the phone down and asked my colleague Kavita who was also in the meeting if she had heard anything new about Bourdain. She hadn’t. “They said something about his legacy”, I told her. “Is he dead?”

And so we picked up our phones, checked Twitter and discovered that Bourdain’s death had just been announced by CNN.

It was Kavita’s reaction that offered the first indication of how people would react.

“Oh my God,” she exclaimed. “I have to call my husband. He was such a Bourdain fan. This is so sad.”

And then, half an hour later, as other news outlets figured out that Bourdain had gone, my phone began ringing with requests for quotes, obituaries etc. My wife called to say how shocked she was to hear that Bourdain had killed himself --- which was the first time I realised that he had committed suicide.

Who would have thought, she said sadly, that he was so unhappy? As the Twitter tributes began pouring in, I composed my own tweet and then dashed off a short obit for Eazydiner. (“You said ‘not a fan’. Then this tweet about his legacy?” The editor who had called me from The Print texted me, a note of indignation in her tone.)

But nothing had prepared me for the reactions on Indian Twitter. I knew that Barack Obama (with whom he had famously eaten noodles in Hanoi) would tweet about Bourdain. And I expected the food world to be in mourning.

But so many ordinary Indians? Why was there such a collective sense of sadness about the death of a man who was, at best, a distant presence in the lives of most users of Indian Twitter?

It took me a day to figure that out. And I began to wonder if those of us in the food world or, like me, on its fringes, had underestimated the impact that Bourdain had around the world.

Within the food world, it was easy to see why Bourdain was so important. Till he wrote an article for The New Yorker that eventually led to his first (and best) book Kitchen Confidential, most foodies had never heard of him. He was the Chef at Les Halles, a New York brassiere of no great distinction and --- as he himself cheerfully admitted --- he was hardly one of New York’s (let alone America’s) top chefs.

In 2000, when Kitchen Confidential came out, food was already a big deal but most food writing came from the perspectives of the restaurant critic, the recipe recorder or the lifestyle commentator. When chefs were written about, they were treated as genteel, creative figures whose aim was to delight their guests. (The exception to this global trend was England where the idea of the chef as a foul-mouthed delinquent had captured the public imagination in the 1990s.)

Nobody bothered to focus on what life was really like in the kitchen: The long hours, the pressure, the tension, the drinking, the lines of coke that chefs did to keep going, etc. Kitchen Confidential dealt with the seamy underbelly of the business. It reminded Americans that even in New York, perhaps the culinary capital of the world, there was more to cheffing than drinking Kir Royales with Daniel Boulud or sitting down to a sushi dinner with Robert DeNiro and Nobu Matsuhisa.

Kitchen Confidential transformed the way Americans viewed chefs. They began to be seen as swaggering, hard-drinking buccaneers who did a tough job in miserable conditions --- and still managed to create great food.

If Bourdain had never written anything again, his contribution to the food scene would still have been significant.

But he went on to do much more.

Most people know Bourdain from his TV shows. What we don’t remember is what food TV was like before Bourdain came along. Most of it consisted of simple recipe-based demonstrations and when presenters left the studio for outdoor locales they followed certain strange and absurd conventions.

| "People missed him for exactly the same reasons that we, in the TV business, respected him. We admired him for tweaking the genre and making it more real." |

Take for instance, the “intro” shot. You will know it because we still rely on it on Indian TV.

The presenter visits, say, a market. His voice-over goes “I went to the top seafood market in the city to meet (say) Jose Lopez, who sells the freshest tuna in the world.”

The camera then shows the presenter going up to a market vendor. The two men shake hands self-consciously. “Hello Jose” says the presenter. “Welcome to my stall. So pleased to meet you,” says Jose.

Now, any moderately intelligent person can work out how fake this shot is. The presenter has clearly met Jose before. An entire camera crew has set up in the market. Jose has been told where to stand. The presenter has begun walking only after the director has shouted “Action”.

And yet this silly shot was typical of all food TV.

Bourdain saw through this silliness. He stopped his producers from including these absurd staged sequences, he recognised that his viewers were not fools and did not talk down to them. His conversations with his guests (or the people he met in the show) were always real and spontaneous and were often filmed with a hand-held camera. In that sense, he brought real experiences to food TV.

He also introduced Americans to the world and its cuisines. It was not as though US food shows had not travelled abroad before. But nearly always, there was a gee-whiz quality to the tone of the show and that strange, staged air to each shot.

Bourdain treated foreign cuisines and foreigners themselves with uniform respect. Whether he was covering El Bulli or a tapas bar in San Sebastian, he treated all Spanish food with the same familiarity and regard. He was not interested in exotica; in his shows, the food of the world was treated in much the same matter-of-fact way that he treated the food of America or say, France.

As former President Obama tweeted after Bourdain’s death: “He taught us about food --- but more importantly about its ability to bring us together. To make us a little less afraid of the unknown.”

More than any other food presenter before him, Bourdain showed Americans that there was nothing to be scared of in the rest of the world. One way to sample the delights of the world was through food. And he focussed on the cuisine as an expression of culture and society, not merely as a collection of dishes.

Some of his shows worked. Some did not. The early episodes of A Cook’s Tour, for instance, have not aged well. I was never one of those fans who loved everything Bourdain did. But as somebody who wrote about food, I recognised that Bourdain had changed the rules of the game. Just as Hunter Thompson had introduced a gonzo element to the sober political journalism of the Seventies, Bourdain had made all food writers go a little gonzo.

Without Bourdain, many of today’s cutting edge food shows --- say David Chang’s Ugly Delicious --- would not have been possible. We would all still be doing tired retreads of episode 465 of Masterchef. (And even with American Master Chef, Gordon Ramsay’s swear-a-minute-aggression only became acceptable once Bourdain redefined how Americans expected chefs to behave.)

But here’s what puzzled me: yes everybody in the food and TV world knew what Bourdain’s contribution had been. But how did that translate into such an outpouring of public grief? Most of the people who mourned Bourdain on social media were not food professionals. And though his shows ended up being repeated on Indian lifestyle channels, none of them was a phenomenon in the way that say the Australia Masterchef is in India. And yet, at the risk of sounding callous, I can’t imagine the same level of public grieving if one of the Masterchef judges went off to the mystery box in the sky.

Eventually, I found the answer in a tweet from the lawyer and foodie Sanjay Hegde: “The reactions to Anthony Bourdain’s death tell us that a man who eats well, shares his food, and gives of his company to many people, is likely to have made many a friend who will genuinely miss him.”

I thought Hegde got it just right. People missed him for exactly the same reasons that we, in the TV business, respected him. We admired him for tweaking the genre and making it more real.

But while our admiration came from a detached, professional standpoint, we failed to recognise that by transforming the nature of food and travel programming Bourdain connected with viewers in a way that was warm and almost primal. So, as Sanjay Hedge tweeted, he came across not just as a man who ate well (which he did; the world’s best chefs lined up to cook for him) but as somebody who wanted to share his experiences and to give of his company, his curiosity and his warmth to viewers.

In the process, he touched people in a way that TV presenters rarely manage. I don’t want to belabour the gonzo parallels but when Hunter Thompson died, his passing also led to a similar and unprecedented outpouring of grief. Like Thompson, Bourdain reached beyond mere journalism (in books and TV) to occupy a special place in people’s hearts.

So was I wrong to be so surprised by the impact that his death had on people?

Absolutely.

Sometimes we get so wrapped up in our own worlds that we only look at people from a professional perspective.

We forget that our profession only exists because there are real people out there who want to read us or watch us.

Bourdain never forgot that. As the expressions of sadness that followed his death remind us, he had a much deeper and meaningful relationship with his viewers that most of us will ever manage.

Name:

E-mail:

Your email id will not be published.

Friend's Name:

Friend's E-mail:

Your email id will not be published.

Additional Text:

Security code:

Other Articles

Other Articles

-

Only five years ago I would have been stuck with Akasaka in Def Col. or Moti Mahal Deluxe in South Ex. Now I have amazing options to choose from.

-

In the pursuit of vegetarianism and vegetarian guests lies the future. And great profit.

-

I think that Indians have less desire to ‘belong’ than Brits do. We don’t need social approval. And this is a good thing.

-

And ask yourself: have I really been enjoying the taste of vodka all these years or just enjoyed the alcoholic kick it gives my cocktails?

-

There is a growing curiosity about modern Asian food, more young people are baking and the principles of European cuisine are finally being understood

See All