There are many reasons to go to Dharamsala.

There are many reasons to go to Dharamsala.

It is one of Himachal Pradesh’s most important towns. It now has its own cricket stadium. It has a beautiful location at the foot of the Himalayas.

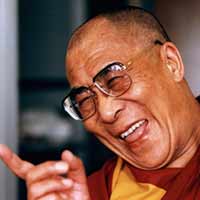

But, in truth, there is only one reason why it has come to so much global attention. In 1960, the Dalai Lama moved to Dharamsala, then a sleepy ghost town, and set up the Tibetan government-in-exile. He chose the suburb of McLeodganj, a few miles away from the main city and the Tibetans built imposing structures, including the house where the Dalai Lama himself lives.

Over time, more and more Tibetans fled from Chinese rule and settled in Dharamsala to the extent that something like 30 per cent of the population is Tibetan. But because the Tibetans are concentrated in McLeodganj, it often feels like there are many more of them, and McLeodganj is known as Little Tibet.

The one time I had interviewed the Dalai Lama was over a decade ago for the Hindustan Times and we met in a hotel room in Delhi. He was on great form, spoke with his usual conviction and the interview caused a splash when it was published.

But the idea of going to Dharamsala had never occurred to me. Then, a year ago, the producer of my TV show, Chetan Dhalla, became obsessed with the idea of a Dalai Lama interview. He began communicating with Tseten Samdup Chhoekyapa, who handles these things for the Dalai Lama. Chetan was told off roundly for even broaching the idea and informed that, at that very moment, the Dalai Lama’s office was handling over 200 requests from all over the world. Did he think he could demand an interview just like that?

But Chetan kept at it and in late February, he got a call. The Dalai Lama was ready to give the interview. But I would have to come to Dharamsala to do it. And there was only a brief window of one or two days when he could do it.

I’ll be honest: I was reluctant to go to Dharamsala. Not because I did not want to interview the Dalai Lama (of course, I did!) but because the best way of getting there is by a small propeller plane and I have terrible claustrophobia. We explored the driving option but that took around 10 to 12 hours. And though our crew finally drove to Dharamsala, I tranquilised myself and took the plane, my nerves numbed by medication.

I stayed at the Fortune Park Moksha, a modern hotel that is probably the best in the area with spectacular views of the Himalayas, and the evening before the interview, I headed to the complex where the Dalai Lama and his aides run their government- in-exile. Tseten took me to dinner at a restaurant next door which he said served authentic Tibetan food.

The food, when it came, was great. I was particularly intrigued by the momos, Tibet’s greatest contribution to world cuisine.

The momo, as we know it in Delhi or Mumbai, is no more than a Chinese-style dim sum. The reason most restaurants describe it as a momo is because this allows them to pack it with all kinds of masaledaar fillings of the kind you could never put into a Chinese dim sum, even in the most renowned Sino-Ludhianvi restaurants.

But Tibetan momos are not meant to be delicate Chinese-style dumplings. They are a simple dish, made all over the countryside, usually with minced yak meat and normal atta. Our momos in Dharamsala had no yak meat but they did not have the masalas we associate with momos in the rest of the India either. More significantly, they were made with atta, not the very fine maida used for momos outside of Dharamsala. So the dough was thick and the dish had a more rustic, less Chinese feel to it.

I asked Tseten if they ate this kind of food every day. His answer surprised me. He ate most meals in the complex’s cafeteria, which was entirely vegetarian. Further, it did not specialise in Tibetan cuisine but served Indian food.

| "At some level, he was also a Marxist, he laughed, because he believed in the advancement of the working class." |

Why was that, I asked. Tibetans are not vegetarians nor does their version of Buddhism require them to abjure meat. He replied that after so many years in India, Tibetans had become more Indian than some of us realised. The Dalai Lama had also turned vegetarian. But some years ago, he fell very ill and was advised by doctors to eat some meat for health reasons.

Early the next morning, I set out again for the Dalai Lama’s complex. My crew who had driven from Delhi (it took them 12 hours) were ready in a meeting room where the Dalai Lama gives audiences to visitors. Except that nobody was sure when the Dalai Lama would actually make it to the interview.

I looked out into the courtyard where a large crowd had gathered. Many (if not most) of those waiting were not Tibetans but were Indians. When the Dalai Lama appeared to meet them, there was a discernible emotional reaction. First, one woman wept on seeing him. Then, the men rushed to touch his feet in the Indian (but not necessarily Tibetan) manner. Next, even more people seemed overcome with emotion.

I watched the Dalai Lama closely. Unlike our own saints and gurus who treat such displays of reverence by solemnly offering blessings, the Dalai Lama made a conscious effort to lighten the mood by laughing and joking with those who were being so serious and worshipful.

He was patient with everyone who had something to say. So patient, in fact, that I began to wonder when the interview would begin. We were already half an hour behind the schedule and there was only one flight out of Dharamsala that day. If the interview did not begin soon, I was going to miss that flight.

When he finished with that group of visitors, I breathed a sigh of relief. But no, it turned out that there was another group waiting to meet him. I guess the Dalai Lama sensed how tense we were getting because as he passed, he stopped by our window, looked directly at my wife, blew his cheeks out, made a funny face and laughed. It took us so completely by surprise that it broke the tension.

When he finally did arrive and we settled down to shoot (over an hour behind schedule), I reminded him of our first interview. Legend has it that each Dalai Lama is reincarnated after he dies. So monks scour Tibet looking for a child who seems to be the reincarnation. But, in Delhi, the Dalai Lama had told me that he was not the reincarnation of his predecessor.

Yes, he said, he had vivid recollections of the life of a previous Dalai Lama, but not of his immediate predecessor. More interestingly, he said, the dreams he now had were not of a Tibetan monk at all but of “the great Hindu master Krishna.” I told him that this kind of figured, because though Tibetans don’t accept this, Hinduism regards the Buddha as an avatar of Vishnu. And Lord Krishna is also a Vishnu-avatar. So from a Hindu (though not Tibetan) perspective, this had a certain logic to it.

Then, we were ready to roll. I won’t say much about the interview because it was telecast a week ago (the deadlines in magazine journalism are very different from those of TV). But once again, he took us by surprise. We were interviewing him on the 60th anniversary of his arrival in India. Grand celebrations had been planned but everything was scaled back in the days before our interview took place. Papers reported that the government of India did not wish to offend the Chinese, who hate the Dalai Lama.

The night before, at dinner, Tsetan had been eager to emphasise that this interview would be about philosophy and not politics. But within a few minutes, the Dalai Lama was talking politics. At some level, he was also a Marxist, he laughed, because he believed in the advancement of the working class. What he objected to was the tyranny of Communist regimes. And on and on he went about China, its totalitarian regime, its oppression of the Tibetan people, etc. etc.

We ended the interview after 46 minutes. I thanked him, but he insisted on staying to meet every member of the crew. He went up to my wife (who comes on most shoots with us) and pinched her cheek. He tickled our principal video journalist Guneet Singh Vedi’s beard and giggled. “Hello sardarji,” he said.

By the time we were finally ready to leave, I was sure I had missed my flight.

But what do you know? It had been delayed by two hours and there was no need to rush.

The Dalai Lama had said before our interview: “You must not worry about things. It will be all right.”

I don’t think he had the flight in mind. But still.....

Name:

Please enter name

E-mail:

Your email id will not be published.

Please enter email

Please enter a valid email address eg. xyz@abc.com !

Friend's Name:

Please enter friend name

Friend's E-mail:

Your email id will not be published.

Please enter friend email

Please enter a valid email address eg. xyz@abc.com !

Additional Text:

Security code:

Other Articles

Other Articles

-

Only five years ago I would have been stuck with Akasaka in Def Col. or Moti Mahal Deluxe in South Ex. Now I have amazing options to choose from.

-

In the pursuit of vegetarianism and vegetarian guests lies the future. And great profit.

-

I think that Indians have less desire to ‘belong’ than Brits do. We don’t need social approval. And this is a good thing.

-

And ask yourself: have I really been enjoying the taste of vodka all these years or just enjoyed the alcoholic kick it gives my cocktails?

-

There is a growing curiosity about modern Asian food, more young people are baking and the principles of European cuisine are finally being understood

See All